BNG Model (a meta-heuristic to find heuristics) [Mental Technique]

What is heuristic?

I’m going to give some examples instead of a definition of heuristic.

Some heuristics are very specific to a domain. For example, there’s a heuristic called the Mehrabian rule that said that ‘what you say is less important than how you say it.’

The heuristic above only applies when you communicate feeling or attitude (if you congratulate others with a disgusted face, do you think people will believe you’re sincerely congratulating them?).

If you follow this heuristic when you want to express your feeling or attitude, then you’ll be able to communicate that feeling or attitude well (e.g. you want to be seen as confident of your capability in a job interview? Speak confidently).

This heuristic doesn’t work for communicating ideas or story (try watching foreign TV shows without any subtitle and see if you can understand the story just by looking at how people say things). The limited usefulness of this heuristic is why I call it ‘specific.’

Some heuristics are more general, such as the heuristics to ‘focus on doing things that give the most impact’ (i.e. the Pareto 80-20 rule). This rule applies in business, relationship, gaming, working, etc. Since this rule can apply to many domains, I call it a ‘more general’ heuristic.

What is meta-heuristic?

When you are thrown into a new situation, you’ll try to find heuristics that apply to that situation. You get a new video game. If there’s a health bar, you probably know that you must ‘keep the health bar above zero’ if you don’t want to die.

Meta-heuristic is a heuristic to help you find such heuristics.

The outcomes of heuristics

Usually, a heuristic produces an uncertain result. The outcome can be bad, neutral, or good.

Some heuristics (e.g. Mehrabian rule and Pareto principle) will (almost) always yield good results. Some things will (almost) always yield bad results (e.g. drinking unfiltered seawater), and if you add “don’t” to doing that thing (e.g. don’t drink unfiltered seawater), you’ll get a heuristics that will (almost) always yield good results.

But most heuristics are more uncertain. It may yield good results some of the time, and it may yield bad results at other times.

For example, “do sport/work out routinely” yields good result most of the time. But if you’re sick, you’d probably be better off eating and sleeping. Another example is “don’t do drugs.” It yields good result most of the time. But if you’re about to be operated, it’s probably a good thing to take the anesthetic drug, so you don’t scream too much and make it harder for the surgeon to concentrate.

The meta-heuristic that I’m about to explain is an elaboration of the idea of ‘most heuristics won’t always yield good or bad results.’ Aside from the two kinds of results explained above (good and bad), I’ll also introduce a third kind of result: neutral results (results that are neither good nor bad).

Introducing the BNG (Bad-Neutral-Good) Model

As written before, the outcome of a heuristic can be either bad, neutral, or good.

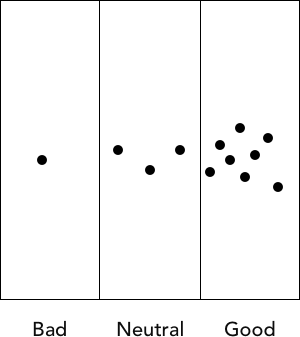

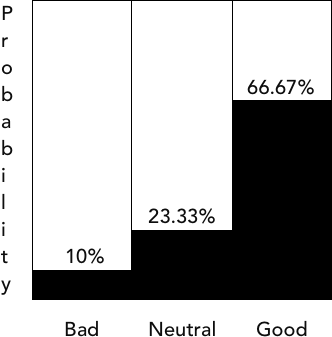

The possible outcomes of the heuristic ‘work out routinely’ can be visualized like this:

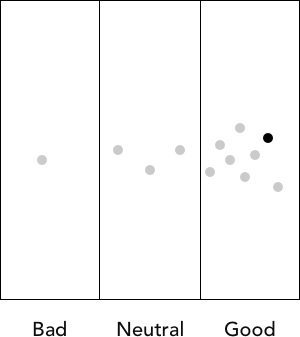

When someone does that heuristic (when he actually works out), the heuristic produces one of the possible results (only one possibility happens). Here the result is good:

The result is influenced by the environment/real life conditions like whether or not it is raining, whether or not the person is sick, what kind of illness does the person suffer, etc.

Using the BNG Model

When you’re thrown into a new situation:

- find heuristics that’ll always bring good results, and then focus on doing them all the time

- find heuristics that’ll always bring bad results, and then focus on avoiding them all the time

Those are the basics. Once you are done with them:

- find heuristics that sometimes bring good results and sometimes bring neutral results, and then also do them all the time (as a safety measure)

- find heuristics that sometimes bring bad results and sometimes bring neutral results, and then also avoid them all the time (as a safety measure)

Once you are done with the safety measures, you can start optimizing even further and become an expert:

- know when the safety-measure heuristics outlined above bring neutral results and ignore them when such situations arise (not doing the sometimes-good heuristic when it won’t bring a good result, not avoiding the sometimes-bad heuristic when it won’t bring a bad result)

- find out heuristics that can bring good results and bad results (and possibly also neutral results), know when to apply (or not apply) them according to the environment/situation (just like the last bullet point explain)

Heuristics that always produce neutral results are things that don’t matter. The only benefit of knowing such heuristics is that so that you know to ignore them. You’d be surprised how many people make a fuss about a heuristic (saying that it’s good or bad), when in fact it doesn’t matter at all (it only produces neutral results). The Pareto 80-20 principle exists because people focus too much on things that don’t matter.

Interestingly, you’ve just finished reading the part of the post that’ll bring the greatest result. The rest of this post is just (a probably unnecessary) elaboration of the BNG model.

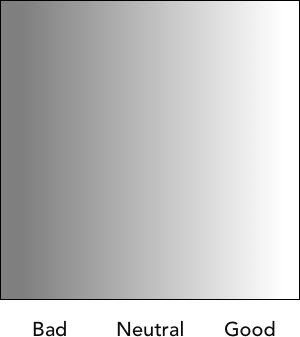

Discrete or Continuous Result

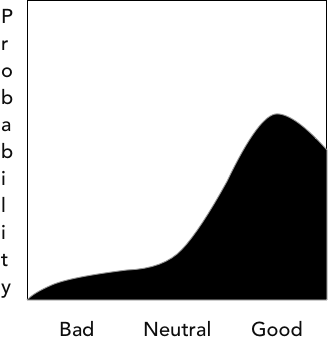

If you want to, instead of viewing the result of a heuristic as discrete (bad, neutral, good), you can view it in a continuous way. The horizontal x-axis then represents the degree of goodness of the result. The vertical y-axis doesn’t mean anything.

But for most purposes, the simpler discrete one is enough.

Using the Y-Axis for Probability

You can even use the y-axis for probability.

With the discrete model, each outcome add up to 1.0 (100%).

With the continuous model, the area below the curve integrates to 1.0 (100%).

But again, simpler is usually better.

Categorizing Heuristics Based on Possible Results

In ‘Using the BNG Model,’ it has been hinted that there we can categorize heuristics based on their possible results. To be exact, there are 7 possible permutations:

- The Yes: things that always bring good results

- The Meh: things that always bring neutral results

- The Nope: things that always bring bad results

- The Bonus: things that may bring good or neutral results

- The Dangerous: things that may bring bad or neutral results

- The Stunt: things that may bring good, bad, or neutral results

- The Roulette: things that either brings good or bad results

7 Permutations Example (Programming)

- The Yes: clean enough code

- The Meh: space vs tab

- The Nope: cryptic variable names

- The Bonus: learning advanced algorithms

- The Dangerous: not indenting code properly

- The Stunt: using cutting edge technology for new projects

- The Roulette: design patterns